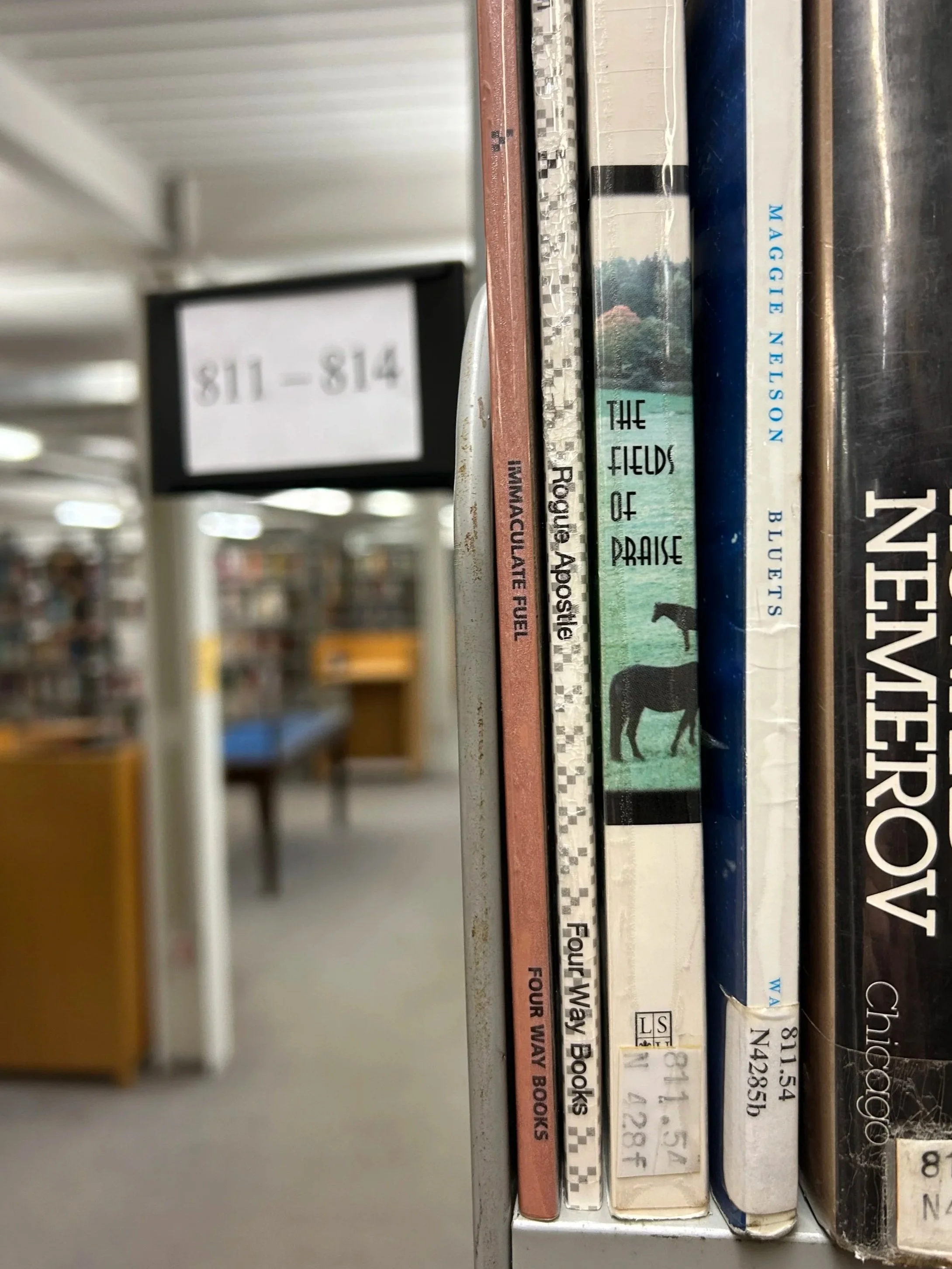

Falling In Love With Maggie Nelson’s “Bluets”

Ryleigh Johnson | September 30, 2025

This piece is the first in a new series reviewing books in the collection of the Pew Learning Center & Ellison Library at Warren Wilson College (WWC). If you would like to submit a book review, email echo@warren-wilson.edu.

The first time I read Maggie Nelson, it was at the suggestion of a philosophy professor who told me that I could learn something from the way she “got weird” with her writing. I didn’t understand at the time what an impact Nelson and her weirdness would have on me, how her work would make me feel understood so deeply. I didn’t know how badly I would need her “Bluets” back then.

“Bluets” is a collage of philosophy, poetry and memoir; a collection of 240 literary fragments composed over the course of three years. On the first page, Nelson writes, “I fell in love with a color-in this case, the color blue-as if falling under a spell, a spell I fought to stay under and get out from under, in turns.”

Ostensibly, the book is about this blue love affair, though blue is perhaps best understood as both an end and a shorthand for the kaleidoscope of topics “Bluets” covers: the devastating end of a relationship; a friend’s life-changing accident; how sadness can saturate every part of a life until it becomes unbearably heavy.

When I read Nelson, I often come away with the feeling that I’ve been transported into someone’s head, listening to the kind of fragmentary recollections and musings that characterize pure consciousness. This style, which at first may be a little disorienting, conveys so much more emotion than a traditional format could. It acknowledges the way that memory and grief distort events and even time itself, leaving in their wake only pieces from which meaning is created.

Much of “Bluets” is addressed to a man Nelson had recently broken up with, who is excoriated in passages like, “Perhaps it is becoming clearer why I felt no romance when you told me that you carried my last letter with you, everywhere you went, for months on end, unopened. This may have served some purpose for you, but whatever it was, surely it bore little resemblance to mine. I never aimed to give you a talisman, an empty vessel to flood with whatever longing, dread, or sorrow happened to be the day’s mood. I wrote it because I had something to say to you.”

As much as “Bluets” is about blue, it’s also about Nelson-how her life feels from the inside, less about the world around her and more about her reaction to it. These raw emotions do not distract from Nelson’s narrative; they are her narrative, soundly rebutting the idea that a personal account of philosophy is somehow less powerful than a dry, academic one. Nelson’s power comes from her honesty, the unflinching way she faces art and pain and the project of living.

Nelson’s other superpower is her command of language. It’s hard not to marvel at the way she synthesizes and shares philosophical musings and deeply personal revelations with the same clarity and rigor. Nelson trusts you to keep up, and there is so much joy to be found in sifting through her recollections. Though her writing, especially in its structure, is unconventional, it never veers into empty provocation.

Nelson is a thoughtful collector of ideas: part of the delight of her work is her vast knowledge of art, psychology, philosophy, history and science. When you read “Bluets,” you get a taste of what it would be to be a true Renaissance woman, both a jack and a master of all trades.

But here comes the moment of confession: when I first read “Bluets,” I wasn’t enthralled. I thought Nelson’s ideas were compelling and her writing was beautiful, but I didn’t understand what she was getting at. I hadn’t fallen in love yet. It wasn’t until a recent re-read that something finally clicked–I read the whole book in one rapturous sitting.

Life often feels wildly tumultuous and when that tumult lives in your head, it can make you feel so very alone. Part of my love for Nelson stems from the unique way that reading her work makes me feel like meeting a kindred spirit, the powerful understanding I experience when I turn her words over and over again in my head. Early in “Bluets,” Nelson describes the phenomenon of a “blue rush,” when miners use dynamite to locate lapis in mines that have seemingly run dry. She then writes, “When I met you, a blue rush began. I want you to know, I no longer hold you responsible.” My advice? Read “Bluets,” and let the blue rush begin.