The Destruction Of Black Asheville

Catherine Lang | Nov. 18, 2025

On Oct. 18, the YMI Cultural Center debuted “Urban Renewal Impact” by filmmaker Todd Gragg and researcher Priscilla Robinson. Supported by over fifteen years of investigation, the documentary brought together community elders and leaders to tell the story of the destruction and displacement of Asheville’s Black communities from 1965-1993.

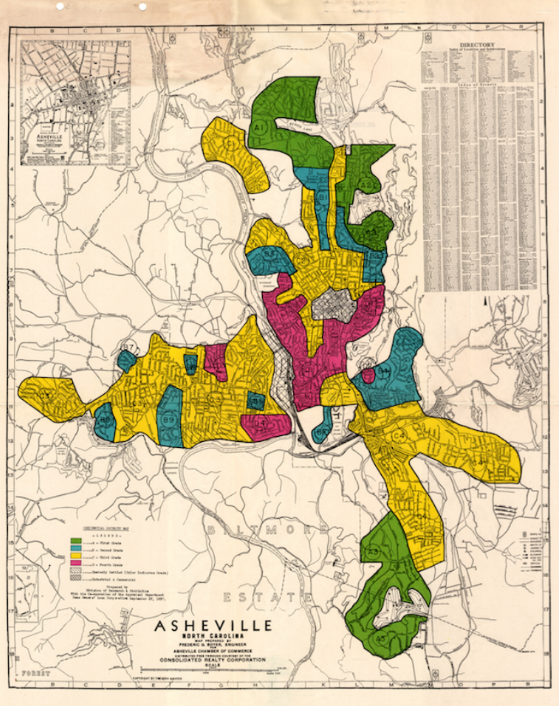

Redlined areas in Asheville circa 1937. (Home Owners Loan Corporation)

Urban renewal was a series of redevelopment projects that followed the Housing Act of 1949. Signed into law by Harry Truman, the act allocated federal resources to local governments to rebuild private infrastructure, promising to provide “a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.” Over four decades, cities across the U.S. engineered similar plans to clear “slums,” targeting low-income, predominantly Black communities.

In Asheville, four neighborhoods were affected: Stump Town, East-End, Hill Street and Southside (East Riverside).

The East Riverside Redevelopment Program began in 1968, designating 407 acres of substandard housing for demolition and reconstruction. The city offered homeowners compensation based on the current value of their property—some homes were appraised for as little as $400, or roughly $4,000 today.

If homeowners refused to sell their homes, the City acted within the legal bounds of eminent domain, and seized their properties.

Redevelopment did not improve living conditions for the residents of these neighborhoods. Over 1,000 families lost their homes, and only 14% of homeowners were able to repurchase property. Robinson described growing up in Southside in a tight-knit neighborhood whose social networks ensured that no one was left homeless or hungry.

“[Urban renewal] killed thriving communities,” Robinson said. “Community was unity.”

According to the late Dr. Reverend Wesley Grant, a prominent civil rights leader in Asheville, Southside “lost more than 1,100 homes, six beauty parlors, five barber shops, five filling stations, fourteen grocery stores, three laundromats, eight apartment houses, seven churches, three shoe shops, two cabinet shops, two auto body shops, one hotel, five funeral homes, one hospital and three doctor’s offices.”

(Sidney) Feldman’s Grocery, 91 Eagle Street in Asheville, N.C. (Andrea Clark/Pack Memorial Public Library)

Businesses that were lost included the James Keys Hotel, the first Black owned hotel in Asheville.

Between 1967-69, the City initiated the Housing Incentive Program, or “Dollar-A-Lot” program, that promised homeowners the opportunity to purchase land for $1 if they committed to building a home.

In Asheville, most Black families were not considered eligible to receive the necessary loans to rebuild on dollar lots. Several decades prior, home ownership programs were developed within the New Deal to prevent massive rates of foreclosures after the Depression. The government issued color-coded maps to banks that limited who was eligible to receive federal loan assistance based on assessed financial risk. Neighborhoods that were predicted to decrease in property value were marked in red and excluded from the benefits of the programs. The majority of “redlined” areas across the U.S. were Black neighborhoods.

Gragg emphasized the prejudiced distribution of land in the 19th century as compounding the effects of urban renewal. As massive parcels of land were seized from Indigenous tribes, the U.S. government issued the Homestead Act of 1862, which stated that any U.S. citizen that had not borne arms against the country could claim up to 160 acres of surveyed land in the new western territories. When the act was passed, Black Americans were not legally recognized as citizens.

Of the estimated 1.3 million deeds that were registered through the Homestead Act, approximately 4,000 were granted to Black families.

“It's easy to see this wealth gap between Black America and white America,” Gragg said. “And people say, ‘Well, that was way back then. Why is that important today?’ Well, the reason it's important today is because if you look at land that's owned in 2025 by white Americans, almost one third of that land can be traced back to the Homestead Act.”

Looking down Eagle Street in Asheville, N.C. (Andrea Clark Collection/Pack Memorial Public Library)

In an attempt to address the inequalities against Black Americans, the Southern Homestead Act was signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1866. Unlike the Homestead Act of 1862, it granted priority land access to freed slaves. Forty-six million acres of land was made available throughout the South, though most potential land owners could not take advantage of the program due to racial hostility, a lack of agricultural tools and resources from extreme poverty, and poor soil conditions on the available land.

The federal government received approximately 6,500 homestead applications, with only 1,000 resulting in deeds. The Act was later repealed in 1876.

Black communities in Asheville today live close to the legacy of urban renewal and centuries of housing discrimination. A total of $6.4 million worth of land was purchased from Southside alone, with 30% of property later being purchased by banks and real estate agencies. Many of these properties have increased in value, some by as much as 400%. Families who lost their home during urban renewal, the film said, were excluded from the possibility to create generational wealth.

In addition to laying the blueprint for urban renewal, the Housing Act of 1949 also issued $120 billion in federal assistance to first-time white homeowners through the Federal Housing Administration. FHA loans were disproportionately denied to prospective Black homeowners.

In 2020, Asheville’s City Council passed a resolution that supported economic reparations to the city’s Black communities, and Buncombe County followed with a similar resolution. In 2022, the Asheville City Council and Buncombe County Board of Commissioners formed the Community Reparations Commission. Members of the commission were appointed to five sub-groups, including education, criminal justice and housing, to investigate how the City discriminated against Black families and neighborhoods, and make recommendations to the City for repairing past harms.

The Reparations Commission released their final report this year, on Sept. 9. Five days prior, the U.S. Department of Justice sent a letter to Buncombe County stating that investigative action would be taken against the county if it approved any of the recommendations made in the 146-page report.

As of Oct. 14, the Reparations Commission has been dissolved; the City will be reviewing the report and deciding whether or not to implement its recommendations on an unknown timeline.

When the topic of reparations came up during the screening of “Urban Renewal Impact,” the audience voiced its distrust, seeing it as another unfulfilled promise made by the City. One audience member called it the “biggest lie to the Black community.”

“Urban Renewal Impact” is the second film in a two-part series by Gragg. Its precursor, “Black In Asheville,” was released in 2023, and further documented the historical discrimination that led up to urban renewal in the 1970s.

Gragg is an independent filmmaker and small business owner dedicated to telling the stories of his city’s Black communities. The film’s lead researcher Robinson received Asheville’s Historical Resources Champion award in 2024 for her commitment to documenting the effects of urban renewal in the historic Southside neighborhood. Documents, photographs and interactive maps can be found on her website urbanrenewalimpact.org.

Installation of “Urban Renewal Impact” mural in Grind AVL coffee shop. (Todd Gragg)

For those interested in further reading, Gragg made several recommendations.

Mindy Thompson Fullilove’s “Root Shock” makes a strong case against displacement policies through examining three U.S. cities impacted by urban renewal programs: Pittsburgh, Newark and Roanoke.

Richard Rothstein's “The Color of Law” describes how federal, state and local governments enforced segregation through zoning, public housing and granted subsidies and tax exceptions to agencies that built whites-only settlements.

In “From Here to Equality,” authors William A. Darity Jr. and Andrea Kirsten Mullen make a case for economic reparations to be made to U.S. descendants of enslaved people, assessing the massive wealth and opportunity gaps between Black and white Americans.

Those who attended “Urban Renewal Impact” on Oct. 18 were welcomed to the YMI, the oldest Black cultural center in the U.S., by its executive director, Rev. Sean Hasker Palmer. Palmer thanked audience members for reckoning with Asheville’s past and present injustices.

“Knowledge is a form of protest,” Palmer said.