A Freewheelin' Woman

Catherine Lang | October 7, 2025

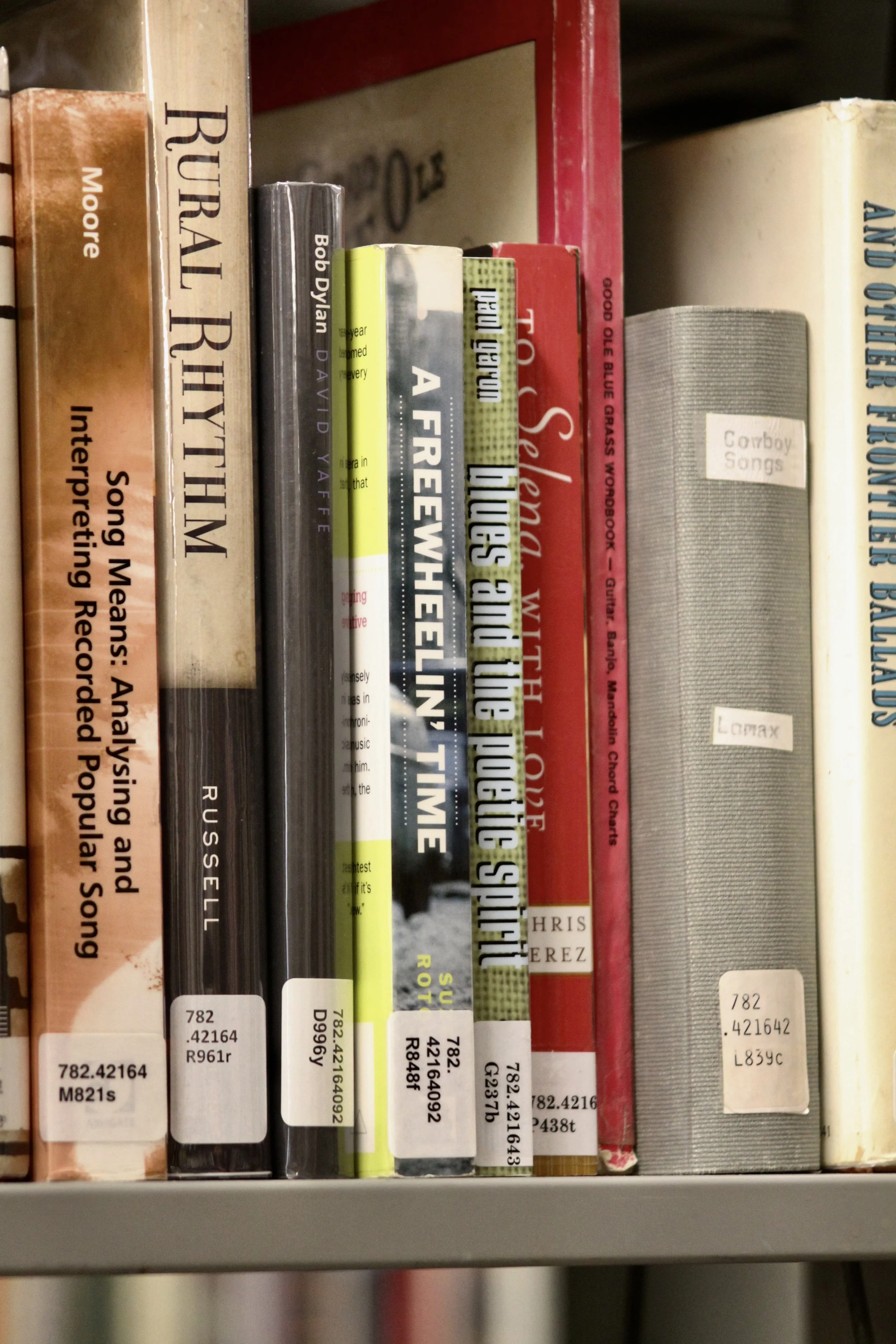

This piece is the first in a new series reviewing books in the collection of the Pew Learning Center & Ellison Library at Warren Wilson College (WWC). If you would like to submit a book review, email echo@warren-wilson.edu.

History will remember Suze Rotolo as the blond girl on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan”—walking arm-in-arm down Jones Street with a rumpled, pre-electric Bob Dylan. In her 2008 memoir “A Freewheelin’ Time,” Rotolo reflects on the years and the relationship that would define her public image for the remainder of her life. With warmth and clarity, she unwinds the complexity of her relationship to the upwardly mobile musician within the greater arc of her own story and provides an insider history of Greenwich Village’s burgeoning folk music scene from 1961–64.

Rotolo first saw Dylan (“Bobby,” affectionately) in the summer of 1961, on stage at Gerde’s Folk City, a restaurant and bar with a reputation for hosting established jazz, blues and bluegrass musicians. Young artists like Dylan made a name for themselves by opening (or playing backup harmonica) for acts like Victoria Spivey, Lonnie Johnson and Big Joe Williams. Between sets, musicians would mingle and jam with one another, merging different styles and eras of music, shaping the new sounds of American folk music that would define the Village culture.

Born a “red-diaper” baby, Rotolo’s parents, Pete and Mary, were members of the American Communist Party. Rotolo was raised in Queens, moving from one working-class neighborhood to another. Her family—all Italian immigrants—faced cultural prejudice and McCarthy-era social blacklisting. Times were hard, especially after the sudden death of her father.

All was endured by the heart of a “very shy and overly sensitive child.” The hardships of Rotolo’s early life were contrasted by a rich cultural upbringing: her father's collections of books and poetry, treasured LPs of opera music and a community of politically conscious adults with diverse cultural backgrounds.

Rotolo and Dylan were both receptive to the rapidly changing world around them, approaching their lives with a sharp curiosity and hunger for artistic expression. Rotolo shared her love of Paul Cezanne, Arthur Rimbaud and Bertolt Brecht with Dylan, who quickly absorbed and imitated new ideas as he was finding his way as a young artist. Rotolo’s upbringing had exposed her to a lot more than a middle-class kid from Hibbing, Minnesota. Her influence would shape the political anthems of Dylan’s early music.

Rotolo was first introduced to the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1958, when she and tens of thousands of other young people marched through Washington, DC, to protest segregation in public schools. She began working for CORE in 1961—the first year of Freedom Rides and sit-ins at segregated lunch counters.

Among a catalogue of odd jobs, Rotolo briefly worked for Peter Schumann, making oversized puppet body parts for the newly established Bread and Puppet Theater.

In June of 1962, Rotolo traveled to Italy for six months to study art in Perugia. As she navigated life on her own, Rotolo read Françoise Gilot’s “Life With Picasso,” a memoir of Gilot’s relationship with the artist, a man labeled by society as “genius.” Rotolo felt a remarkable similarity between Gilot’s account of Picasso’s irresistibly flawed character and that of her own gifted-male-artist boyfriend.

“He took no responsibility,” Rotolo wrote, paraphrasing Gilot, “clarified nothing, came to no decisions and did nothing that would make it possible or easier for the various women he was involved with to leave him or get on with their lives. He was a magnet, and the force field surrounding him was so strong it was not easy to pull away. His art was the main function of his life.”

After the release of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” Dylan’s popularity soared. People approached Rotolo as a means to get closer to him. She saw herself relegated to the role of a musician's “chick,” without encouragement or momentum to pursue her own life’s work. It would be another decade before the women’s movement brought a collective voice to her experiences.

Roloto ended her relationship with the singer before the release of “Another Side of Bob Dylan.” The two stayed in touch through the following years; Rotolo was a sympathetic friend to Dylan as he navigated fame, obsessive fans and people’s expectations of him, while Dylan offered financial support to Rotolo after her apartment was destroyed in a fire.

In 1964, Rotolo joined Albert Maher and Jerry Rubin in an attempt to visit Cuba. The U.S. Government had instituted a ban on all travel to the country the previous year, as a response to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Rotolo believed that the U.S. feared the implications of its citizens seeing the progress made after the country’s socialist revolution. This included the Cuban Literacy Campaign, which dropped illiteracy rates in Cuba from 30% to almost 0%.

At a press conference in New York’s Kennedy Airport, Rotolo announced that she and four others would be crossing into Cuba that day. At each of their stops in London, Paris and Prague, Rotolo was followed by U.S. embassy offers under order by the FBI. Outside of their legal jurisdiction, Rotolo refused to give the officers her passport or comply. A total of 84 students made it to Cuba without interference.

Rotolo and her peers were greeted by the international press and met with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro’s brother Raúl. They toured factories, schools and a nickel mine. Guevara explained to the students how Cuba’s leadership was attempting to meet the cultural needs of its population; the head of agricultural planning had decided to grow white rice because unrefined grains and flours were still closely associated with poverty. When she returned to America two months later, Rotolo’s passport was stamped as invalid.

Rotolo once received a call from a man with an English accent. The phone operator said his name was George Harrison, and he was staying at the Delmonico Hotel with his band and Bob Dylan. Harrison invited her to visit and bring her girlfriends. Enormous crowds outside the hotel made it almost impossible to enter. When Rotolo phoned the musicians' room from the lobby, Dylan chided her for not coming alone. Rotolo hung up the call and went home.

Suze Rotolo writes with a natural grace, revealing the intimate stories of her youth with an acute balance of humility and frank observation. Her voice moves with a calm authority, always true to herself and to the dynamic personalities who crossed her path. For a brief moment, readers can step into the remarkable lives of the last generation of Village bohemians, as painted by Suze, in which she is the revolutionary voice of her time, not Bob.

“A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties” by Suze Rotolo is available to borrow from the Pew Library.